Founder Mode Meets Bank Mode: Capital One Buys Brex

Brex’s workflow layer meets Capital One’s balance sheet.

Deal snapshot

On January 22, 2026, Capital One announced a definitive agreement to acquire Brex in a stock‑and‑cash transaction valued at $5.15 billion, consisting of approximately $2.75 billion in cash and 10.6 million shares of Capital One common stock.

Announced deal terms:

Aggregate consideration: $5.15B.

Consideration mix: ≈$2.75B cash + ≈10.6M Capital One shares.

Expected closing window: middle of calendar year 2026, subject to customary closing conditions and regulatory approvals.

Post‑close leadership: Pedro Franceschi will continue to lead Brex as part of Capital One.

Capital One’s characterizes the consideration as ~50% cash / ~50% stock.

“Since our founding, we set out to build a payments company at the frontier of the technology revolution… Acquiring Brex accelerates this journey, especially in the business payments marketplace.”

“Together, we’ll maximize founder mode by combining Brex’s payments expertise and spend management software with Capital One’s massive scale, sophisticated underwriting, and compelling brand…”

What is Brex, really?

The joint release describes Brex as “a modern, AI‑native software platform offering intelligent finance solutions” that helps businesses issue corporate cards, automate expense management and make secure, real‑time payments. It explicitly calls out AI agents used to automate complex workflows, reduce manual review, and control spend.

Brex’s product bundle:

A card and payments product (transaction processing, controls, rewards).

Spend management software (policy, approvals, receipt capture, accounting integrations).

Cash / treasury plumbing that blends banking partners and a broker‑dealer structure (depending on product).

An “AI layer” positioned as workflow automation.

Brex’s disclosures emphasize that Brex is a financial technology company and not a bank; elements of the Brex business account are provided through partner institutions, while certain cash management and securities features are provided through Brex Treasury LLC (a broker‑dealer registered with the SEC and a FINRA/SIPC member).

This matters for an acquirer. A bank already has a low‑cost funding base and a deep compliance apparatus. A fintech can build product velocity, but it rents regulatory permission. An acquisition can convert “renting permission” into “owning permission,” or at least owning the integration between permission and product.

Brex publishes periodic broker‑dealer Statements of Financial Condition for Brex Treasury LLC. The July 31, 2025 statement shows total assets of about $58.7M and member’s equity of about $55.2M. This is not Brex’s consolidated balance sheet, but it gives one clear signal: the regulated broker‑dealer entity is structurally modest relative to a $5.15B acquisition price. The value being purchased is the operating platform and distribution, not a pile of broker‑dealer net assets.

Scale signals

The joint release states that Brex serves over 25,000 companies and operates in more than 50 countries. That is scale, but it’s not the same as profitability. Still, it’s enough to infer product‑market fit and a non‑trivial support and risk footprint.

The customer list in the release includes recognizable names (DoorDash, TikTok, Anthropic, Robinhood, CrowdStrike, Zoom, Plaid, Intel, and others). Brex is attempting to be credible in the mainstream enterprise tier, not only in venture‑backed startups.

Capital One’s context: scale, timing, and the post‑Discover moment

The acquirer is not a mid‑cap fintech buying growth with expensive equity. Capital One is a major U.S. bank. In the press release, Capital One describes itself as a “leading technology‑based financial services company” with $475.8B in deposits and $669.0B in total assets as of December 31, 2025, and emphasizes that it is “the only major U.S. bank to migrate entirely to the public cloud.”

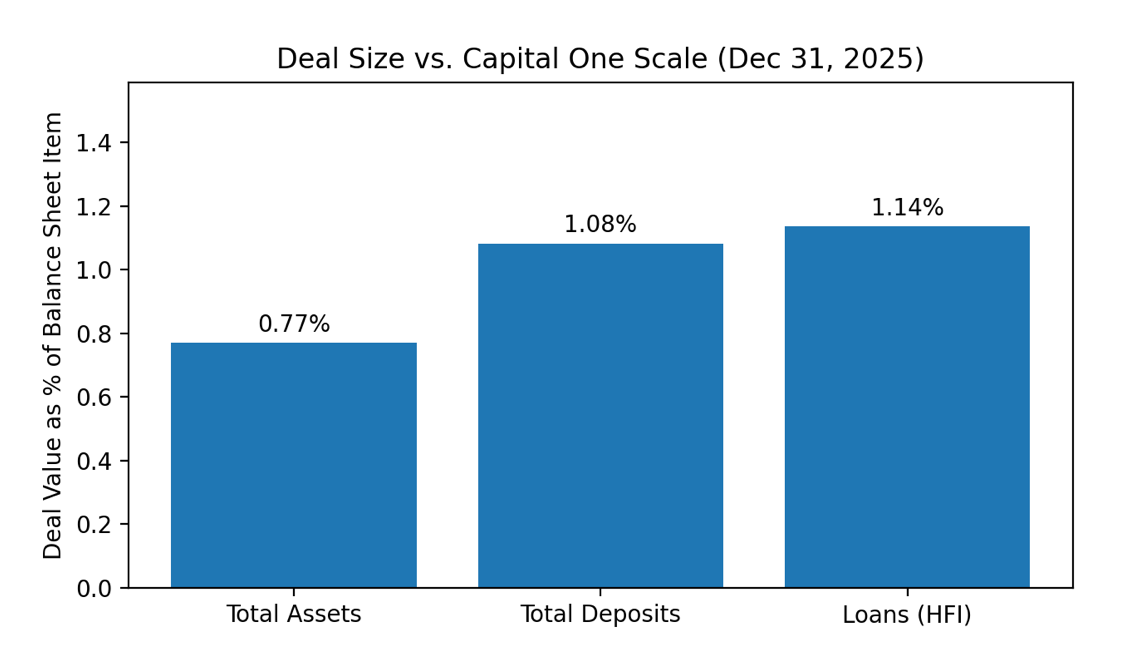

The deal is small relative to the balance sheet, but not small relative to managerial attention.

One way to stay sane when a number like $5.15B is floating around is to anchor it to the acquirer’s scale. As a percentage of Capital One’s assets and deposits, the deal is around 1%, financially digestible. Operationally, however, it lands in the middle of a multi‑year integration cycle.

Timing: this happens right after Discover.

Capital One’s Q4 2025 materials note that it completed the Discover acquisition on May 18, 2025, and that Discover results are included from May 18, 2025 to December 31, 2025. This is relevant because bank integrations are not Lego. They are plumbing. Plumbing is where value quietly leaks if you don’t keep your best engineers and risk people focused.

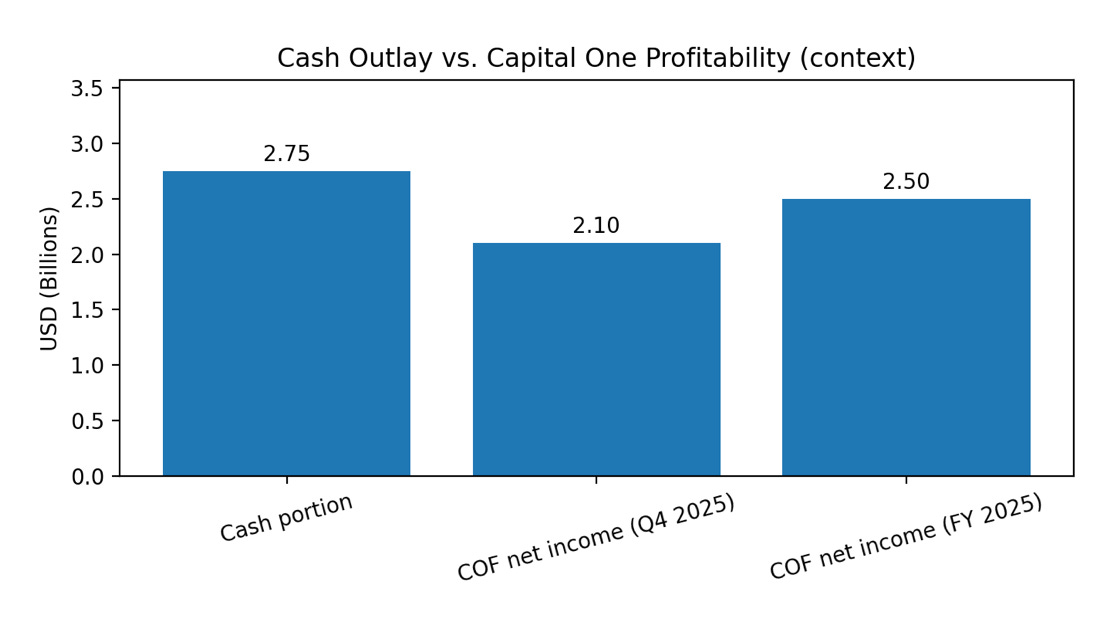

Capital One’s Q4 2025 earnings presentation reported net income of $2.1B for Q4 2025 and $2.5B for full‑year 2025. Those numbers are a reminder that the cash component of the Brex deal (~$2.75B) is not existential, but it is large enough that execution drift becomes an expensive hobby.

The strategic logic (and the parts that have to go right)

Fairbank says acquiring Brex “accelerates” Capital One’s journey to build a payments company, “especially in the business payments marketplace.”

“They have taken the rarest of journeys for a fintech, building a vertically integrated platform from the bottom of the tech stack to the top.”

That line is doing a lot of work. “Vertically integrated” is a claim about defensibility. If the stack is real, it implies faster iteration and fewer vendor dependencies.

A useful decomposition: what Capital One may be buying

Think of Brex as three assets bundled together:

A distribution channel into fast‑growing companies.

A workflow layer (spend controls, accounting automation, approvals).

A payments engine that touches the money in real time.

Capital One already has the balance sheet, underwriting, and regulatory infrastructure. Brex already has the product surface area where finance teams actually live.

Where this can compound

Here is the optimistic compound mechanism:

Capital One’s funding + underwriting expands Brex’s credit capacity on a risk‑adjusted basis.

Brex’s software reduces operational friction for customers (and can reduce servicing costs).

AI‑driven workflow automation increases retention as workflows become encoded.

Discover network assets create optionality for routing and economics.

A combined sales motion pulls spending + deposits + software into one relationship.

If (1)–(5) reinforce, you get something banks struggle to build internally: a high‑frequency software product sitting on top of a regulated balance sheet.

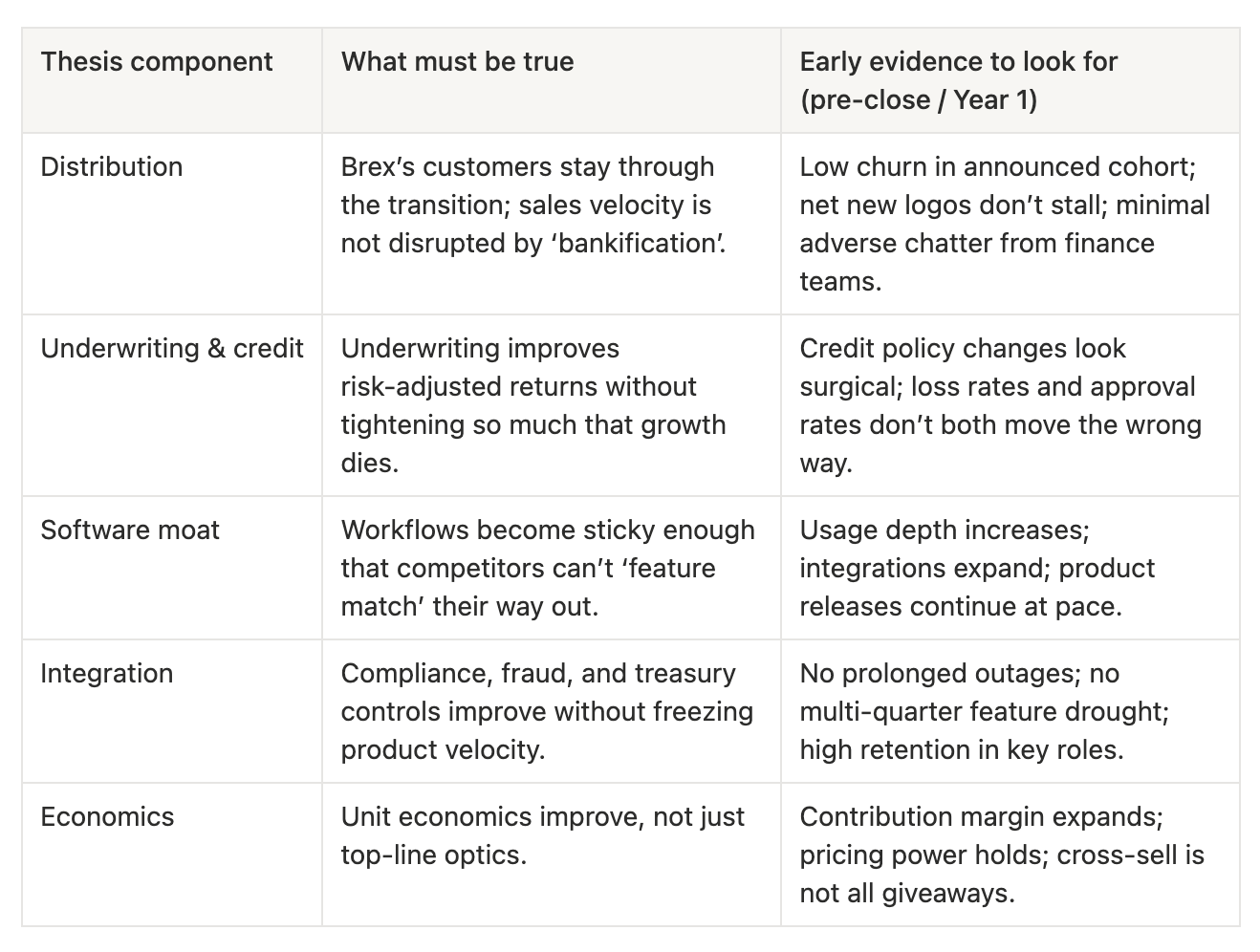

The non‑optional parts (what must be true)

If you read the table and think “that’s obvious,” you’re already halfway to the right posture. Most acquisition failures are not mysterious. They are obvious in hindsight, and subtle in real time because nobody wants to be the person pointing at the leak.

Buffett’s framework is helpful for corporate acquisitions because it’s basically the same activity: you are buying a business. The stock market noise is irrelevant. What matters is (a) the economics of the business, (b) the people running it, and (c) the price you pay.

Circle of competence: is Brex understandable to Capital One?

At the surface level, yes: corporate cards and payments sit squarely inside a bank’s map of the world. But the deeper question is whether Capital One understands the software distribution dynamics well enough to avoid turning Brex into a bank product, because banks are good at balance sheets, not always at product surfaces.

Moat analysis: what could be durable here?

Brex’s potential moat is not that it issues cards (many can). It is that it becomes the operating system where finance teams set policy and run workflows. If you encode approvals, budgets, ERP integrations, travel policies, and receipts into one system, switching becomes painful. That’s a software moat: switching costs + embedded process.

Capital One’s release describes Brex as “vertically integrated… from the bottom of the tech stack to the top.”If that’s true, it suggests competitors can’t simply copy the UI and buy the rest as vendors. But the burden of proof is high: fintech history is full of “full stack” claims that were actually a pile of vendor contracts plus a nice dashboard.

Management: the highest‑leverage ingredient is staying put

The announcement says Franceschi will continue to lead Brex after the transaction closes. That single line may be one of the most economically important sentences in the entire disclosure. If Brex’s advantage is product velocity and founder conviction, leadership continuity is part of the purchased asset.

How does this blow up?’

“Invert, always invert” is the habit. So invert the press release. Assume it is 2028 and the deal is widely viewed as a disappointment. What likely happened?

Product velocity slowed because compliance and bank governance introduced friction; competitors out‑shipped Brex.

Customer churn spiked around contract renewals as CFOs sought ‘bank‑independent’ alternatives.

Credit performance worsened in a downturn; underwriting tightened; growth stalled; unit economics didn’t improve.

Key engineering and risk leaders left; the remaining team shipped fewer meaningful improvements.

Integration with Capital One systems created outages or degraded customer experience.

Capital One management attention was consumed by Discover integration and regulatory workstreams; Brex became a side project.

The deal’s thesis was cross‑sell, but sales motions did not translate; Brex’s funnel was different from a bank’s.

The core incentive tensions:

Founders: preserve autonomy and product speed while gaining scale.

Bank leadership: de‑risk compliance and reputation; avoid surprises.

Risk & compliance teams: minimize tail risk, which can mean saying ‘no’ by default.

Sales: push distribution; may discount heavily if targets are aggressive.

Engineers: stay if they can still ship; leave if they become ticket‑closers.

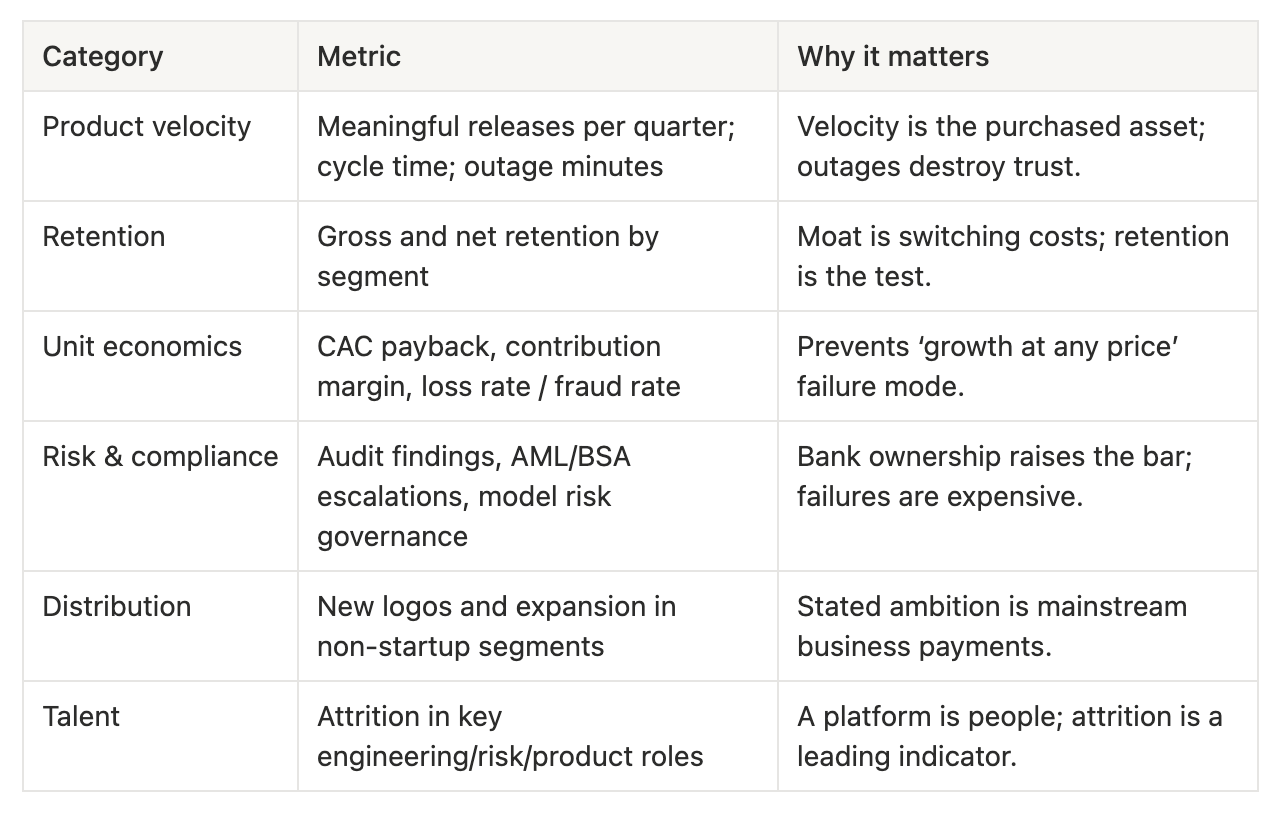

If you want one practical test: watch whether product leaders still have clear ownership and whether the company can still make decisions quickly. When decision latency rises, innovation dies quietly, and then everyone blames the macro.

Checklist questions for management and investors

What is the single biggest incentive mistake we could make in integration design?

Which decision rights remain with Brex leadership, and which are centralized?

How will we measure product velocity post‑close (release cadence, time‑to‑ship, defect rates)?

What is the ‘one‑year integration budget’ in both dollars and senior‑leader attention?

The capital allocation trade: what else could Capital One do with $5.15B?

The CEO’s menu:

Reinvest in the core business.

Acquire other businesses.

Repurchase shares.

Pay dividends.

Pay down debt / build capital.

An acquisition is justified when it beats the next‑best alternative on a risk‑adjusted, per‑share basis.

We don’t have enough disclosed Brex financials to compute an expected per‑share return directly. But we can still evaluate whether the structure looks disciplined. Using ~50% stock and ~50% cash, and issuing ~10.6M shares, suggests Capital One is trying to balance three constraints: (1) preserve capital flexibility, (2) avoid an all‑stock ‘we’re overvalued’ signal, and (3) keep Brex stakeholders aligned with post‑close performance.

Will Brex be run for per‑share value or for headline growth?

If Brex is run as a growth trophy, the failure mode is predictable: heavy subsidies, lots of ‘strategic’ spend, and no durable unit economics. If Brex is run for per‑share value, you should eventually see pricing discipline, tighter underwriting with clear risk‑adjusted returns, product investments that reduce servicing costs, and retention improvements that show up in lifetime value. In other words: you’ll see boring metrics improve.

A pre-mortem

Regulatory and closing risk

The transaction is subject to required regulatory approvals and customary closing conditions. Bank‑fintech acquisitions can trigger questions about consumer protection, data privacy, AML/BSA compliance, model risk (especially with AI), and payments concentration.

Integration risk: the silent killer

There is a specific integration risk that is easy to underestimate: decision‑making speed. Brex likely wins because it can ship product, adjust risk policy, and iterate quickly. Large banks often win because they are durable and compliant, at the cost of slower change.

If the combined company cannot preserve Brex’s decision speed while upgrading its control environment, then the acquisition destroys the very asset that justified it.

Competitive risk: software moats are earned, not declared

Brex competes in a category where competitors can ship fast and spend aggressively. Even if Brex has product advantages, competitors can attempt to brute‑force growth with incentives. The defensive move is to deepen workflow lock‑in and deliver measurable savings to customers (time, errors, headcount).

Credit and cycle risk: business payments touch real losses

Unlike many SaaS categories, corporate spend products are entangled with credit and fraud risk. If underwriting tightens during a downturn, growth can stall; if underwriting loosens to hit growth targets, losses can spike. Capital One’s claim of “sophisticated underwriting” is one of the core synergy arguments. That synergy only exists if it improves risk‑adjusted returns, not just approval rates.

Cultural risk: founder mode meets bank mode

Franceschi frames the combination as “maximizing founder mode.” That is a motivating narrative, but also a cultural fault line. The acquisition works best if Capital One can provide infrastructure and distribution while resisting the urge to re‑platform Brex into the bank’s existing product cadence.

What to monitor through close and Year 1

Pre‑close (now → mid‑2026)

Regulatory process: pace, requests for information, and any changes to expected closing timing.

Integration architecture: do they commit to keeping Brex’s product surface and velocity?

Key leader retention: engineering, risk, product, and sales leaders stay.

Customer communication: clarity around continuity of service, pricing, and support.

Year 1 post‑close

If you want an even simpler heuristic: the deal is working if Brex feels more capable (faster product, broader underwriting, better economics) without feeling more bureaucratic. If it feels more bureaucratic, the risk is that the market re‑prices it as ‘just another bank card’.

Sources:

Capital One Financial Corporation, Form 8‑K (Jan 22, 2026) — includes transaction consideration details. https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/927628/000119312526019543/d97758d8k.htm

Joint press release (Exhibit 99.1) — quotes from Richard D. Fairbank and Pedro Franceschi; deal timing; company descriptions; COF deposits/assets; Brex customer scale.

https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/927628/000119312526019543/d97758dex991.htmCapital One Q4 2025 Earnings Release Presentation (dated Jan 22, 2026) — includes deal mention and selected financial metrics used for context charts.

https://fortune.com/company-assets/1767/quartr/slides-f7326-2026-01-22-09-58-09.pdfCapital One — Q4 2025 earnings release / financial supplement (dated Jan 22, 2026) — includes Discover acquisition timing notes and detailed financial tables.

https://fortune.com/company-assets/1767/quartr/press-release-1169984793-2026-01-22-09-58-09.pdfBrex blog post announcement (Jan 22, 2026): “Brex is joining forces with Capital One.”

https://www.brex.com/blog/brex-is-joining-forces-with-capital-oneBrex Treasury LLC Statement of Financial Condition (as of Jul 31, 2025) — filed pursuant to SEC Rule 17a‑5(e)(3).

https://go.brex.com/rs/166-VEV-188/images/H1_FY26_BT_SoFC_FINAL.pdf?version=0Brex Treasury LLC Statement of Financial Condition index page (lists recent statements; includes disclosures about banking partners and broker‑dealer status).

https://www.brex.com/statement-of-financial-condition

Sharp anaysis on the decision latency risk. The point about measuring product velocity post-close is the real tell here becuase that's where most fintech acquisitions fail quietly. Banks optimize for risk mitigation but fintechs win on iteration speed, and thats almost impossible to preserve inside bank governance without deliberate structural choices.