Dreamer: The OS for AI Agents

Personal intelligence as a platform play. Owning the layer where models meet your calendar, email, and files.

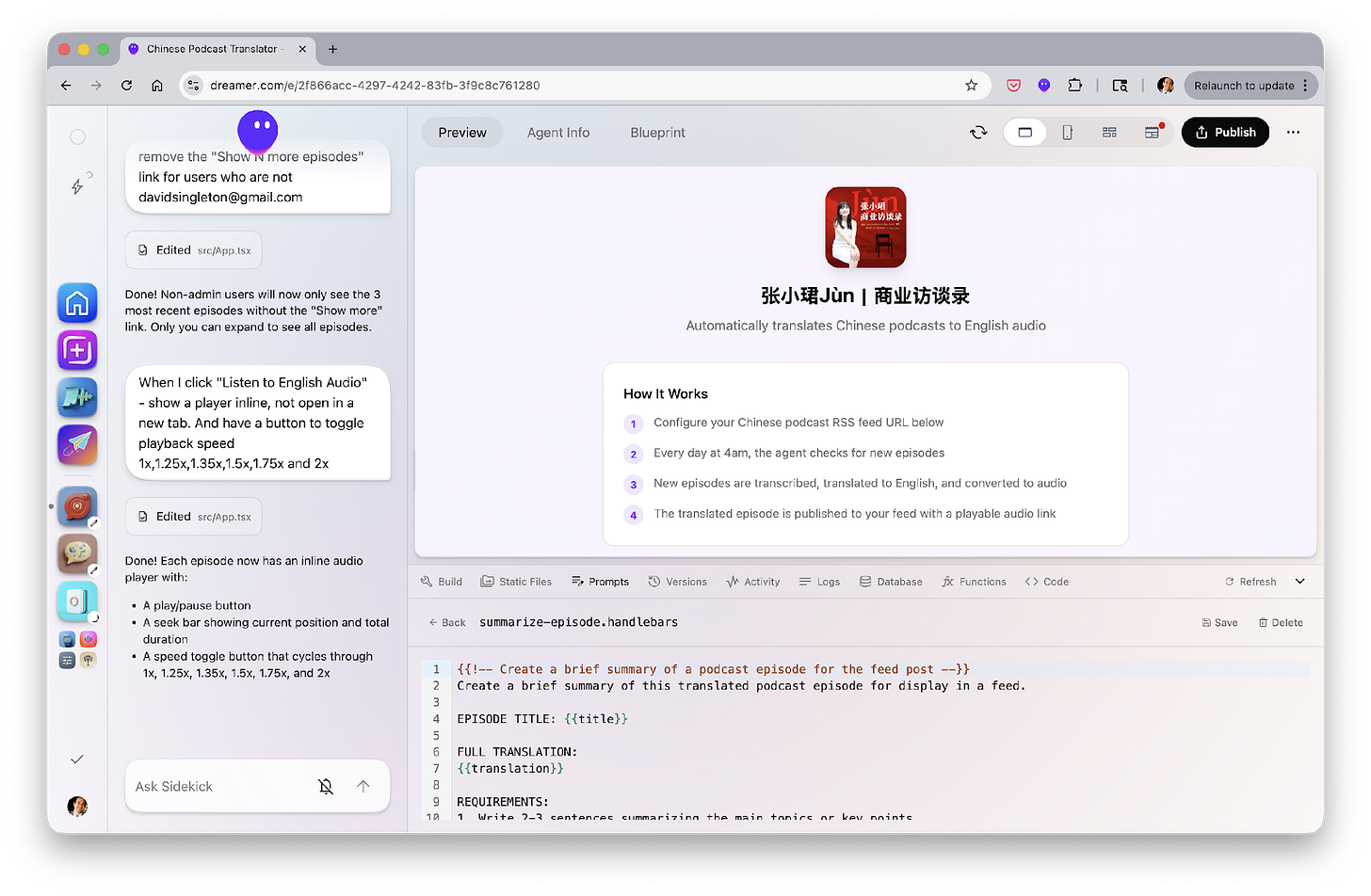

Dreamer is a cross-device operating system that lets people create, run, and share AI agents that can securely use real-world tools and personal data. Dreamer is “your home for personal intelligence” and the company is an attempt to revive an old dream: end-user malleability of software.

Your Tools Don’t Talk (and You’re the Router)

Dreamer’s canonical customer is the smart, non-technical person who can articulate a problem but cannot translate it into a working system. David Singleton uses his sister as the stand-in: she can instantly name tasks she’d like to automate, but has no way to start.

A second customer is the builder: engineers (and increasingly non-engineers) who can vibe code a prototype, but struggle to ship a durable, integrated, permissioned product that works across devices and keeps working next week.

Current alternatives:

Chatbots and copilots: great at answering questions, weaker at safely taking multi-step action across your accounts; often require repetitive context re-entry; limited memory, limited permissions auditability.

DIY automation (IFTTT, Zapier, scripts): powerful but brittle; steep setup curve; hard to blend deterministic logic with probabilistic model behavior; difficult for non-technical users.

Agent frameworks (LangChain/LangGraph, AutoGen, etc.): developer-centric; require hosting, auth, state, UI, observability, and safety work that is largely non-differentiating but unavoidable.

OS and productivity suites (Apple/Google/Microsoft): deep integration, but agents are not first-class; extensibility and interoperability are constrained by platform politics and app-silo boundaries.

No-code app builders: can produce a web app; usually don’t solve ongoing background work, user-specific memory, real-time tool access, or cross-agent composability.

Dreamer’s critique is simple: today’s software is designed for humans, not AI, so agents must awkwardly adapt to interfaces of the past. A new foundation is required.

Sidekick + Tools + Agents: An OS Shape for AI

Natural-language programming crossed a usability threshold (vibecoding): state-of-the-art models can now read, write, and modify code at expert level, making end-user software creation plausible. Software itself has shifted toward intelligence-native systems (Karpathy’s “Software 3.0”): agents that can reason, adapt, and run while you sleep. LLMs exist and the system primitives to make them safe, composable, and cross-device do not. Dreamer tries to supply those missing primitives.

Dreamer’s operating-system mapping:

Dreamer as Operating System

dreamer.com ~= Graphical User Interface [GUI]

Agents ~= User space

Sidekick ~= Kernel

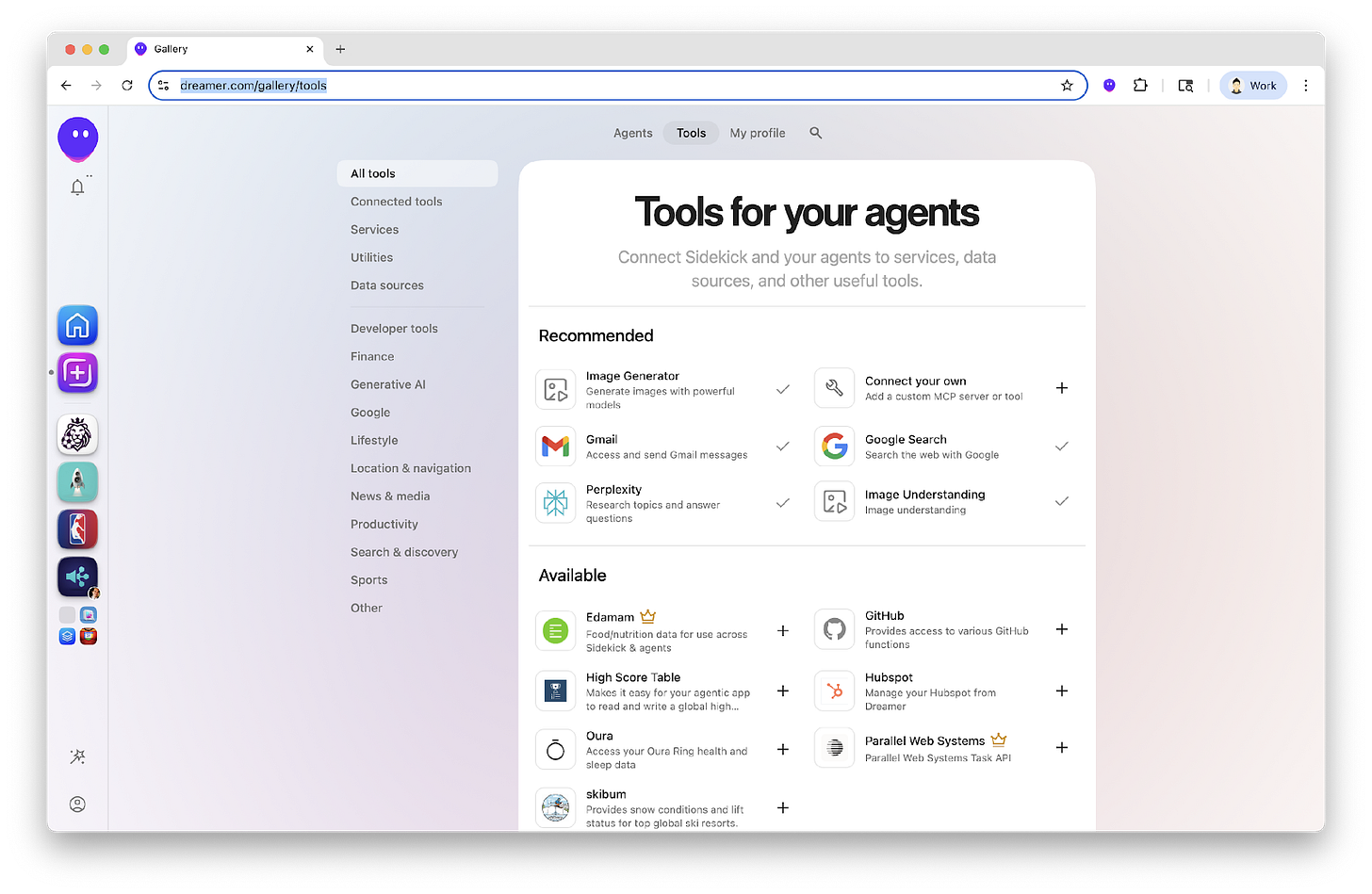

Tools ~= Device Drivers

From that mapping, the unique value proposition becomes legible:

Agents have triggers, deterministic code, prompts, sub-agents, UI, and a database, meaning they can be long-lived, stateful, and interactive.

Tools are a base-layer integration system with explicit permissions, designed to avoid the “scrape and pray” approach to data access.

Sidekick is a system-level agent that can both build other agents and mediate cross-agent collaboration safely, acting as the only entity with access to all tools and all agents.

Everything runs in the cloud with per-user isolation, so users don’t have to host compute, inference, or storage.

Dreamer’s plausible moat ingredients are:

Composability: if each agent exposes functions that the rest of the system can use, new agents increase the utility of old ones (and vice versa). That’s a compounding flywheel.

Personal memory + workflow embedding: once Sidekick accumulates inspectable, user-controlled memory, the platform becomes more valuable and more costly to switch away from.

Permissioned tool ecosystem: high-quality integrations are both hard to build and hard to commoditize when wrapped in trust, auditing, and distribution.

Cross-device UI primitives: an agent that works cleanly on desktop and mobile without bespoke engineering is rare; if Dreamer nails it, it’s a durable developer platform advantage.

The counterpoint is that moats invite siege engines. Incumbents own distribution and identity. Dreamer’s endurance depends on whether it becomes the default place users go to manage agentic life, before the incumbents fold the pattern into existing homescreens.

Dreamer’s public roadmap hints are concrete:

Android app “very soon” (already in internal use).

Watch and other fast-input surfaces “coming soon.”

Economic infrastructure: paying tool creators via subscription share; monetization for agents “coming.”

The strategic direction is equally clear: a marketplace-like ecosystem where tools and agents are created by third parties and monetized, with Dreamer as the trusted OS layer.

Dreamer’s founders lean on lived examples rather than abstract promises:

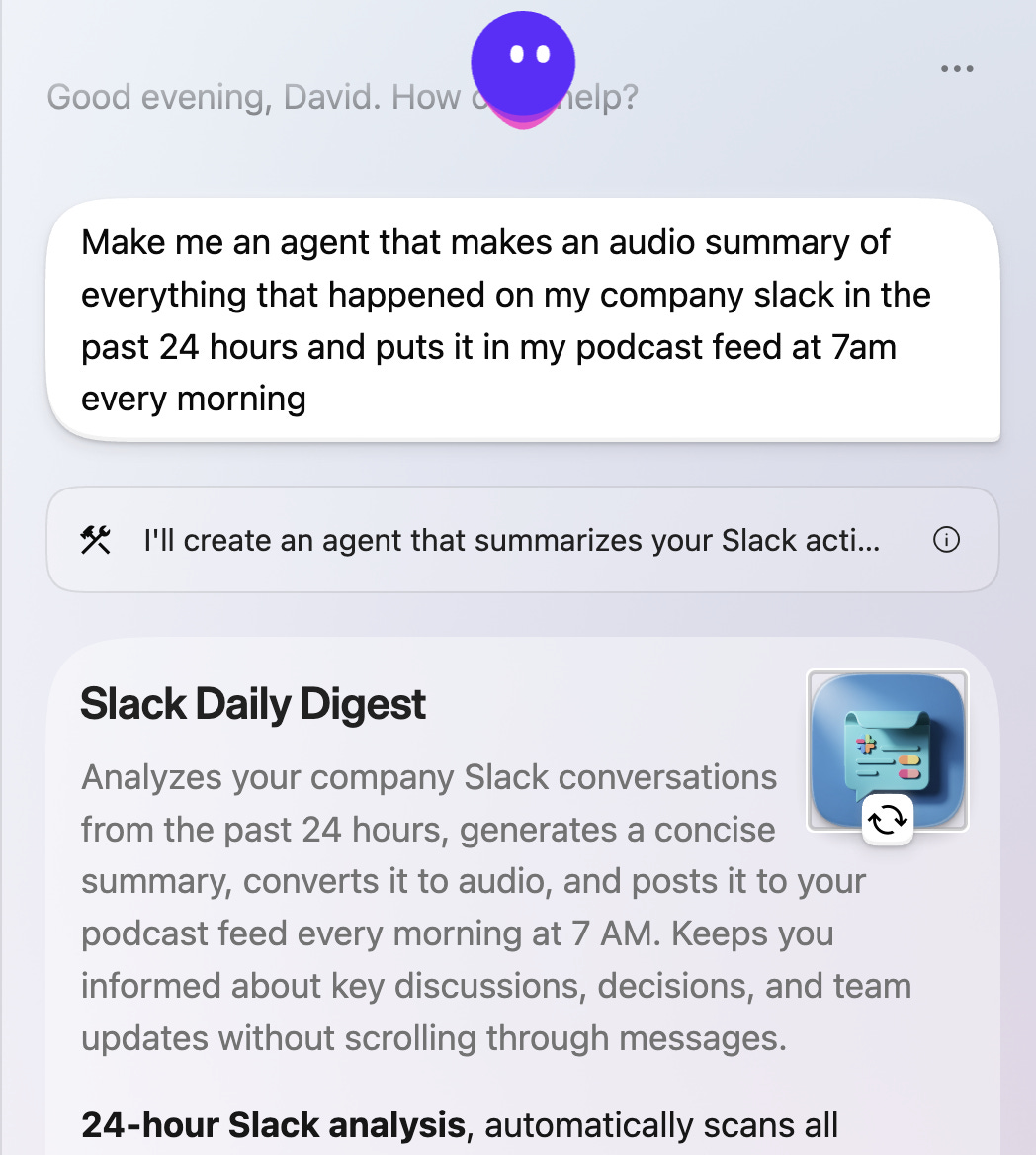

A daily audio briefing agent that summarizes calendar, news, and Slack into a podcast feed.

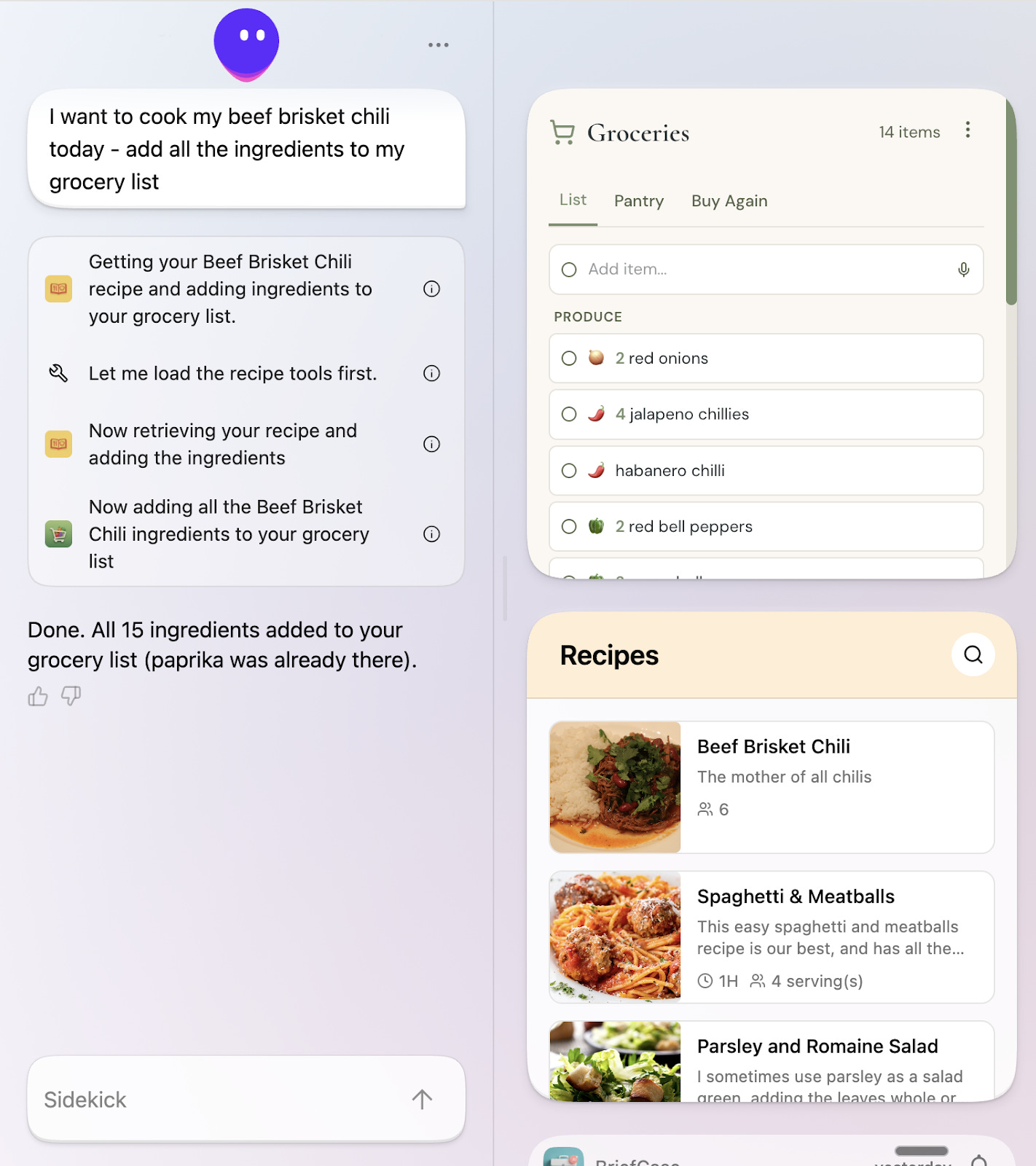

A recipe agent that parses recipes from the web and a grocery list agent that can be populated automatically by asking Sidekick.

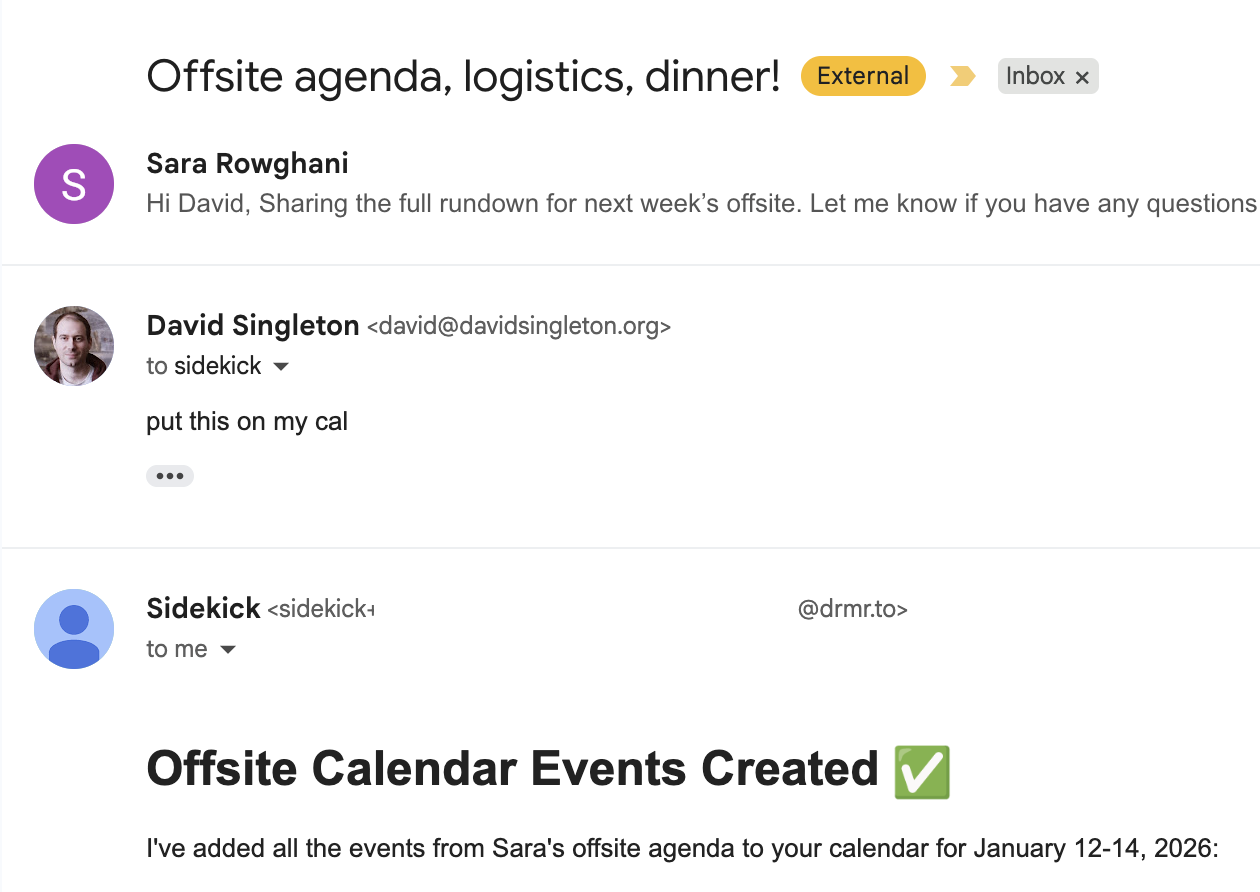

An email-driven workflow: forward an email to Sidekick with “put this on my calendar,” and have it execute.

Dreamer sits in three places at once:

Cloud runtime: agents run in isolated VMs with provisioned storage and compute.

User interface: a desktop web app at dreamer.com plus mobile apps (iOS TestFlight today; Android coming).

I/O surfaces: browser extension, mobile sharesheet, feed + RSS/podcast feed, and email-to-Sidekick.

Dreamer’s own examples cluster into a few archetypes:

Personal operations: calendar triage, email sorting, reminders, life admin.

Information distillation: personalized news, meeting prep, daily digests, “read later” agents.

Cross-system workflows: Slack-to-podcast, email-to-calendar, web-to-recipe-to-grocery.

Creative and playful agents: story books, image style transforms, games and environments.

Business mini-systems: CRM, BI dashboards, ticketing; integrating tools like Google Workspace, GitHub, Linear.

2026: Models Grew Hands, Users Grew Impatient

The Xerox PARC dream stalled because programming was too hard for most people. In the last ~12 months, models crossed a threshold where natural language can reliably produce working code, making end-user malleability plausible again.

The missing ingredient was reliability. If the model can’t write code well enough, then an “OS for personal agents” becomes a liability factory: broken automations, security leaks, and hallucinated actions. Dreamer is betting that model capability, tool ecosystems, and user willingness to delegate have finally met in the middle.

The historical evolution of the category:

1970s–90s: End-user computing dreams (Smalltalk, HyperCard, Visual Basic): powerful but still demanded a “programmer brain.”

2000s–2010s: Web automation and workflows (macros, scripts, IFTTT/Zapier): useful, but brittle and integration-heavy.

2010s: Voice assistants (Siri/Alexa/Google Assistant): broad reach, shallow autonomy; hard to customize deeply.

2022–2024: LLM copilots: language competence becomes mainstream; developer tooling explodes.

2025–2026: Agentic systems: models move from “answer” to “act,” and platforms start to treat agents as first-class.

Three measurable trends:

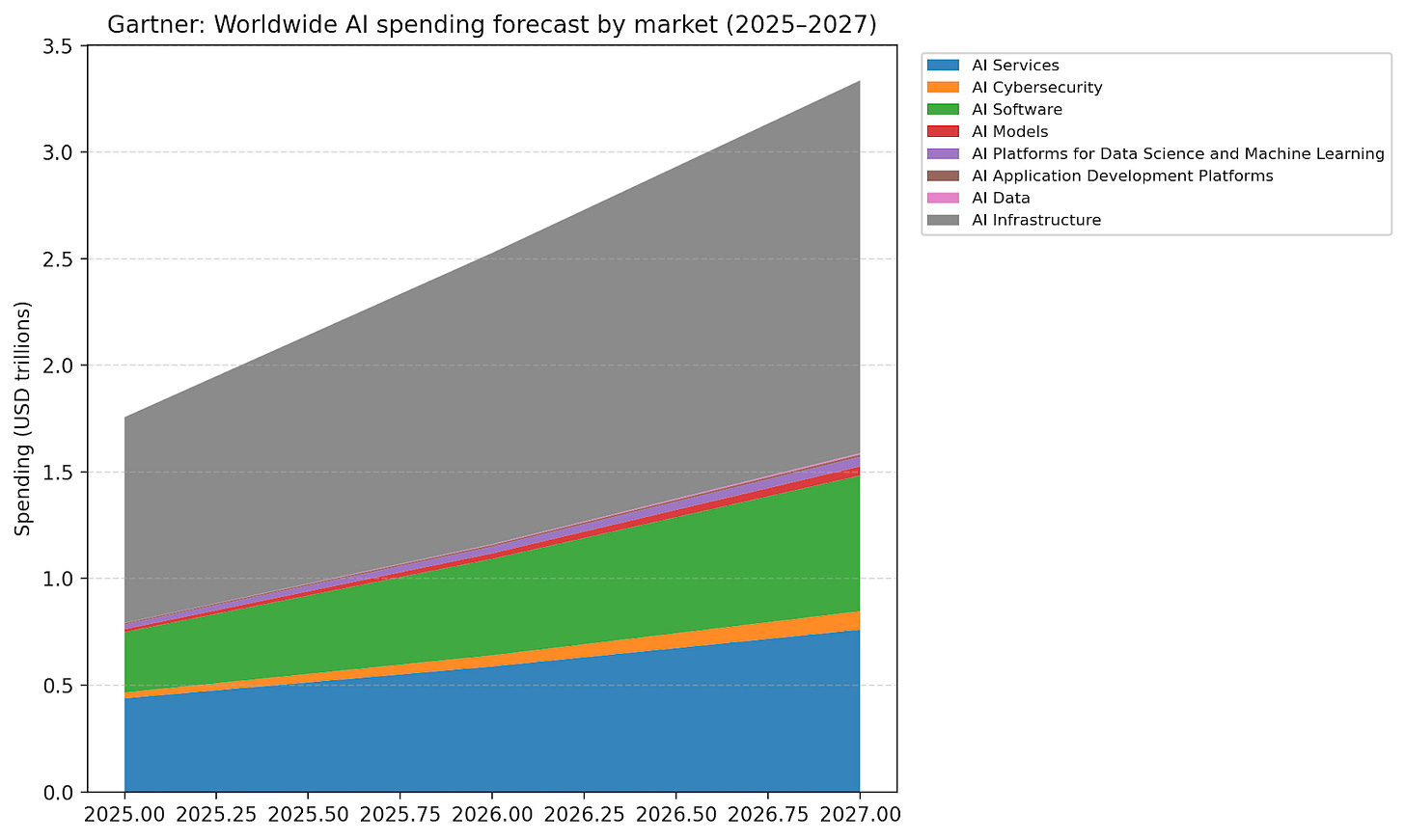

AI spending is now measured in trillions: Gartner forecasts $2.52T of worldwide AI spending in 2026, rising to $3.34T in 2027.

Software spending continues to grow rapidly: Gartner forecasts worldwide software spend of ~$1.43T in 2026.

Developers are normalizing AI tools: Stack Overflow’s 2025 survey reports 84% of respondents are using or planning to use AI tools in development, up from 76% the prior year.

The Prize: Replatforming Personal Software

Dreamer serves three overlapping constituencies:

End users (initially power users): people who want “personal intelligence” that can act across devices and accounts.

Builders: developers and tinkerers who want to ship agents with UI, storage, triggers, observability, and safe tool access without reinventing the platform.

Tool providers: companies that want distribution for their capabilities as “premium tools” inside agentic experiences.

Dreamer is both a consumer product and a developer platform. That makes it potentially large.

Dreamer is attempting to name a category into existence: a personal-agent OS that feels like a homescreen, but where apps are AI-native and personalized. If the metaphor holds, the closest historical analogs are smartphone OSs and app stores, except the apps are living processes, and the API surface includes your real data.

The target persona implied by Dreamer’s onboarding is:

Someone with lots of digital exhaust (email, calendar, Slack, docs) and recurring small decisions.

Someone willing to delegate and to tolerate early imperfections if the system feels like leverage.

Someone who cares about privacy and wants explicit control over what touches what.

Often (today) a builder: Dreamer explicitly says the beta waitlist is being processed to keep the community focused on builders.

Dreamer’s set of tool targets and early distribution channels:

Built-in and planned integrations: Google Workspace, GitHub, Linear, plus data sources like sports scores, transit data, and movie showtimes.

Third-party tool partnership: Parallel Web Systems for agentic search and tasks.

Surfaces: Chrome extension, iOS app (TestFlight), desktop web app, email interface.

Because Dreamer is early, market sizing is more about bounding a bet than pretending precision. Here is a transparent three-layer model:

TAM (top-down): AI software and platforms spend.

Gartner forecasts worldwide AI software spending of ~$452B in 2026 (within total AI spending of ~$2.53T). Dreamer is best viewed as competing for a slice of the AI software layer plus the “AI application development platforms” layer.

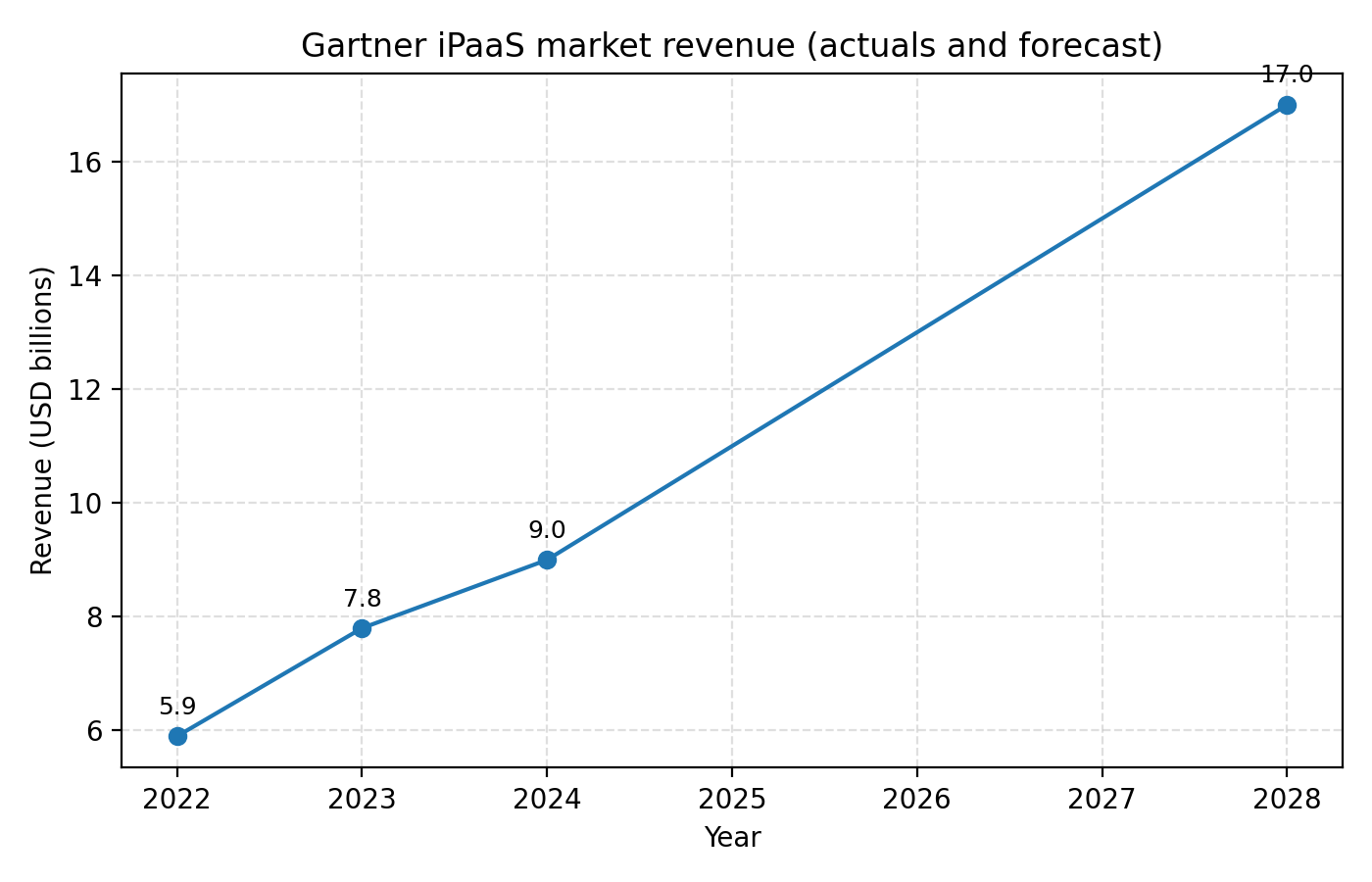

As a sanity check, consider an adjacent market Dreamer may partially cannibalize or complement: integration (iPaaS). Gartner estimates iPaaS revenue exceeded $9B in 2024 and forecasts it to exceed $17B by 2028.

SAM (bottom-up): early adopter builder + power user segment.

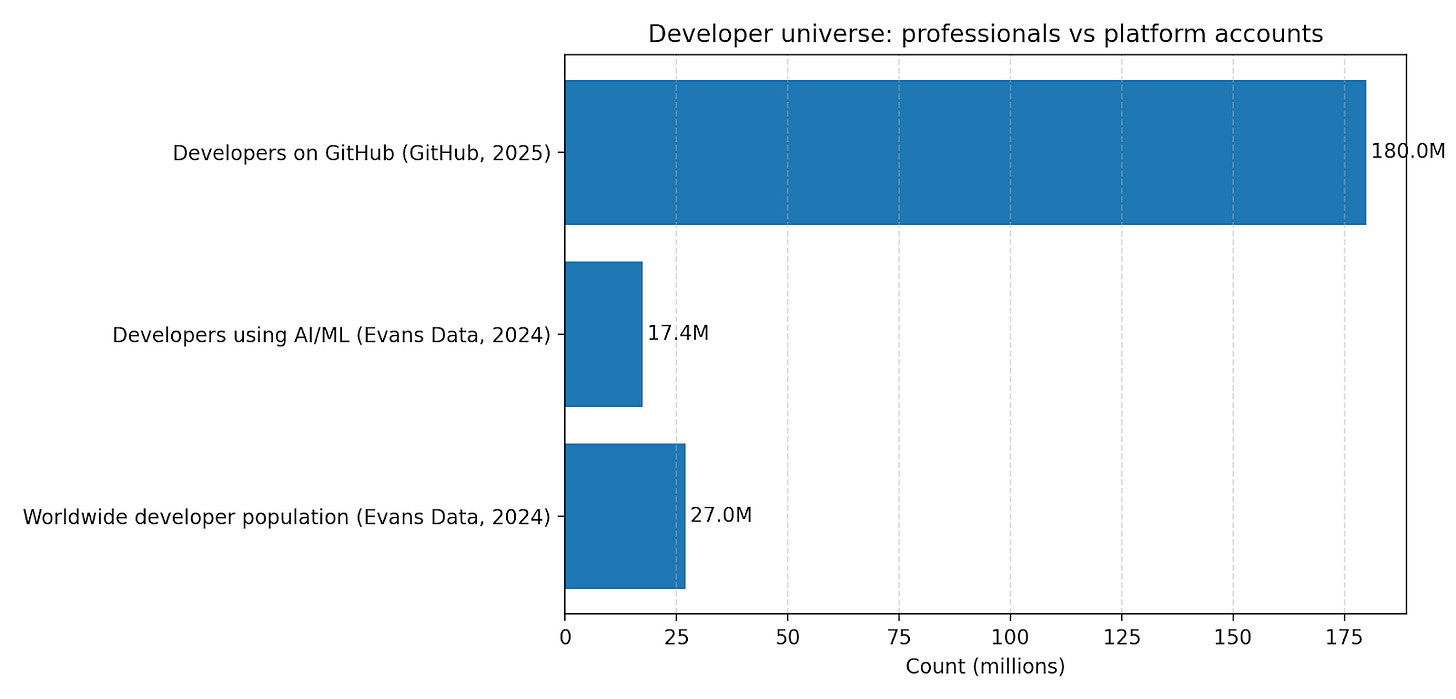

Evans Data reports a worldwide developer population of ~27M in 2024, and estimates over 17.4M developers are using AI or have built AI/ML applications.

A conservative SAM model for Dreamer’s first phase:

Addressable early adopters: 5–15% of the 17.4M AI-using developers (0.87M–2.61M) who are already experimenting with agentic workflows.

Assumed pricing band: $10–$30 per user per month for a paid personal intelligence subscription (Dreamer says the beta is an extended free trial of a paid product).

Implied SAM range (annual recurring revenue): ~$104M–$940M ARR (0.87M–2.61M users × $10–$30 × 12).

These are scenario bounds constrained by disclosed base rates and Dreamer’s own paid-product intent.

SOM (serviceable obtainable): a 3–5 year capture within that SAM.

Can the company earn trust, distribution, and retention before competitors crush margins? A plausible SOM in 3–5 years might be 1–3% of the SAM user range above (9k–78k paying users on the low end; 26k–156k on the high end), depending on product-market fit and distribution. At $20/month, that is ~$2M–$37M ARR. Again: a scenario, not disclosure.

The Arena: Giants, Workarounds, and Agent Studios

Dreamer is building at the intersection of several crowded maps. Competitors show up in layers:

Direct (agent platforms + marketplaces): systems where users can create or install agents/apps and run them with integrations.

Indirect (incumbent OS/suite assistants): Apple/Google/Microsoft assistants and automation features; strong distribution and identity, weaker end-user malleability.

Developer ecosystems: agent orchestration and hosting frameworks; great for engineers, not a consumer OS.

Automation and integration platforms: iPaaS/RPA tools that already connect accounts and execute workflows, increasingly augmented with AI.

Work “homepages”: products that aggregate tasks and context (inboxes, calendars, dashboards) but don’t expose agentic composability.

A particularly relevant signal is that large developer platforms are explicitly moving toward “agent orchestration” as a first-class concept. GitHub’s Agent HQ pitch is that the AI landscape is fragmented and needs a unifying workflow; that’s a cousin of Dreamer’s OS thesis.

Dreamer’s plan to win is visible in its chosen constraints:

Treat safety and permissions as OS primitives (tool permissions, memory access mediated by Sidekick), not as application-level afterthoughts.

Make agents composable by default (functions), so the ecosystem compounds rather than splinters.

Ship multi-device UX as a platform primitive (agents with rich UIs that work on phone and desktop).

Invest early in community + economic incentives: pay tool builders via a share of subscriptions; provide credits to agent creators; build toward monetization.

Dreamer’s competitive advantages:

OS-level architecture clarity: Sidekick-as-kernel and tools-as-drivers makes permissions and composition explicit.

Batteries included: hosting, inference access, database, UI primitives, triggers, observability.

Multiple I/O surfaces (email, feed/podcast, browser extension, mobile sharesheet) that integrate into existing habits.

Cross-agent interoperability enforced by design (functions + Sidekick mediation)

Platform economics (early): subscription revenue share for tool creators; credits for agent creators.

Inside the Machine: Processes, Drivers, and Guardrails

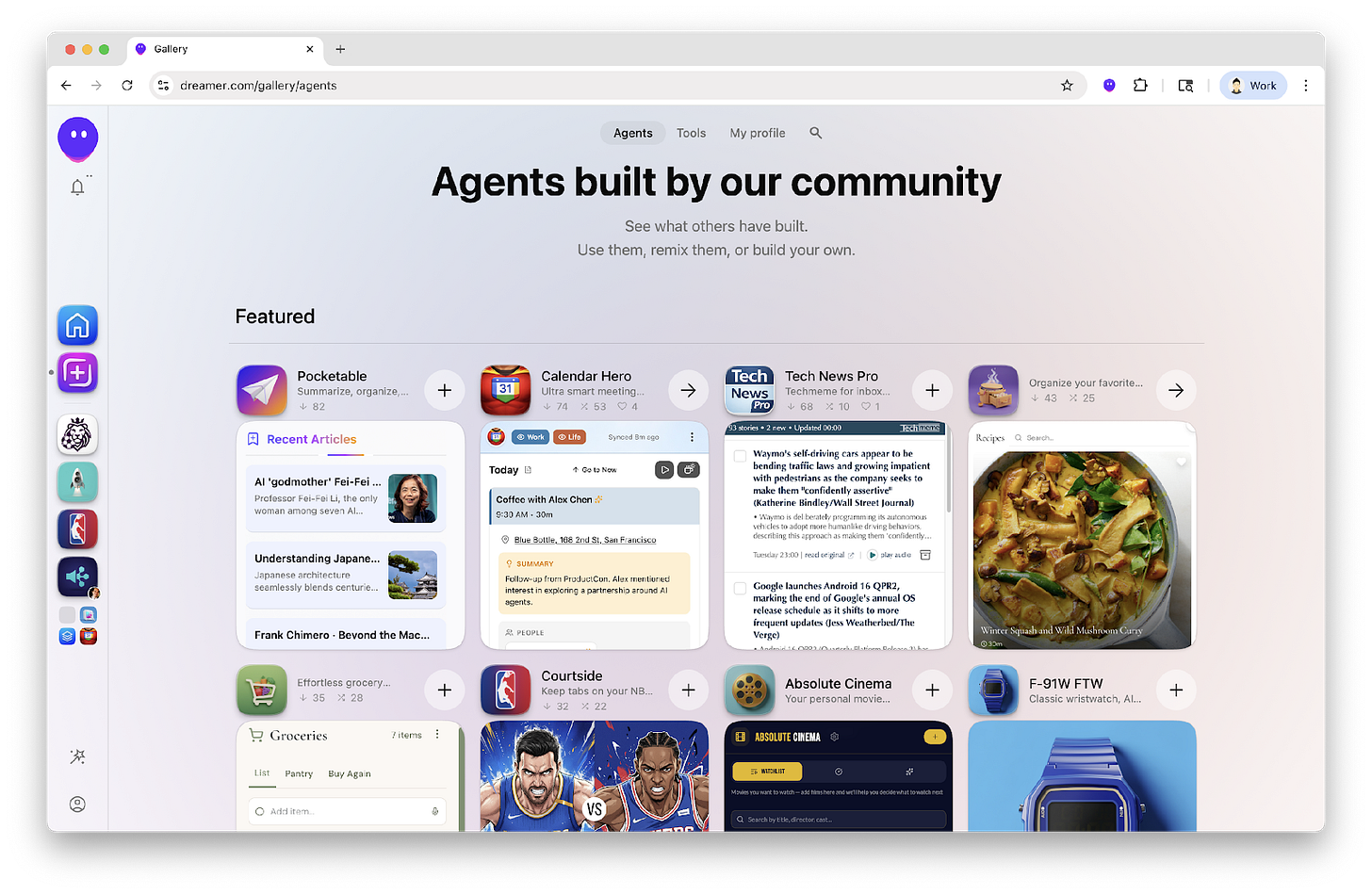

Dreamer’s product line-up is better understood as surfaces over one OS core:

Desktop web app (dreamer.com): dashboard, Sidekick chat, Gallery, settings, rich agent editor.

Browser extension (Chrome): send web pages to agents; file drag-and-drop into Sidekick.

Mobile apps: iOS via TestFlight today; Android “very soon.” Includes widgets and sharesheet integrations.

Feed + RSS/podcast: agents can post audio to feed; system exposes an RSS feed you can subscribe to in podcast apps.

Email interface: each user gets a unique email address to send tasks to Sidekick.

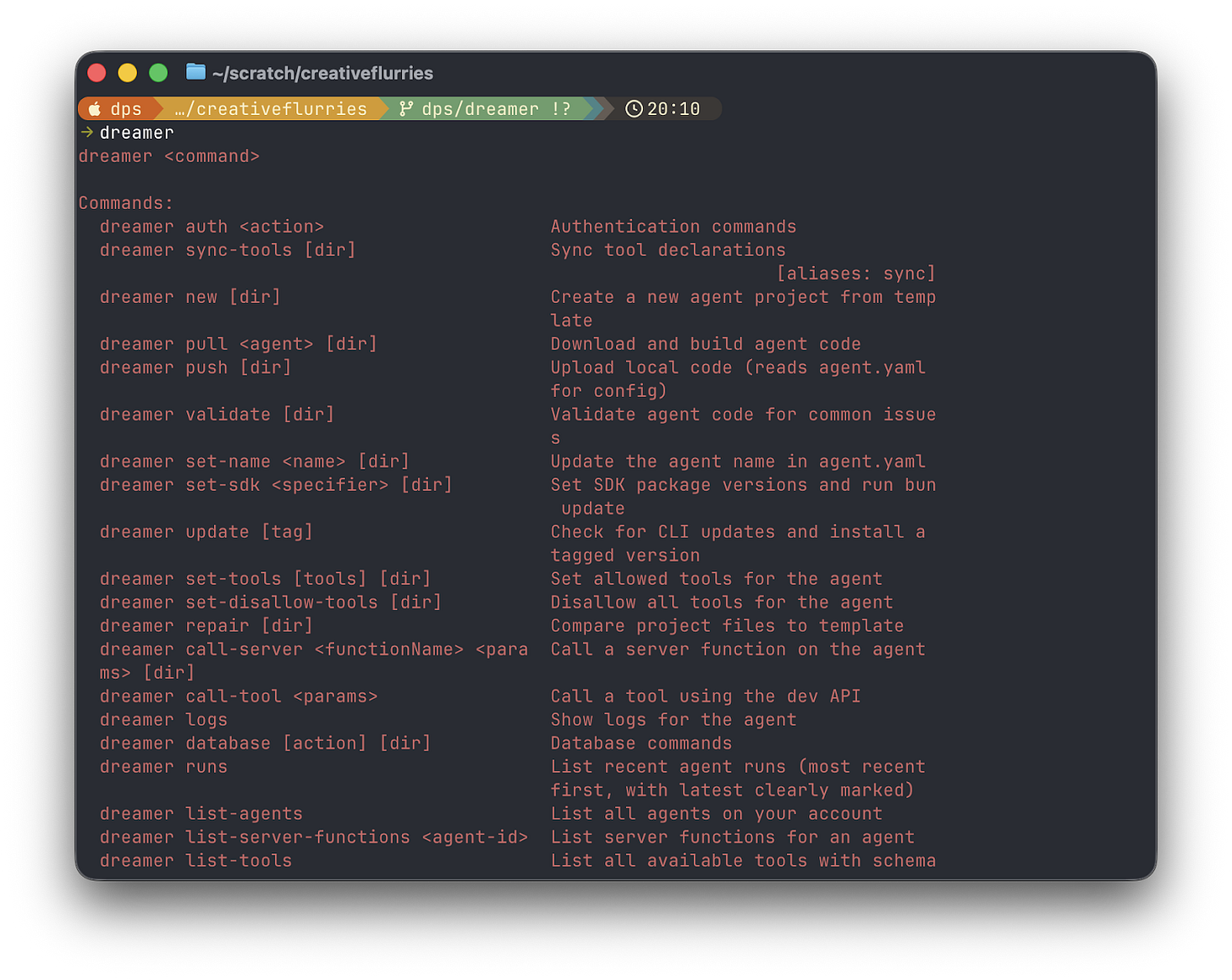

Developer CLI: for building and syncing tools/agents from local code.

Core feature primitives:

Tools: built-in and extensible integrations; tool permissions; MCP server + optional skills + branding assets.

Agents: triggers, deterministic code, prompts, sub-agents, UI, database/static files; isolated VM runtime.

Sidekick: system agent with full tool/agent access; builds agents; mediates collaboration; available via chat, voice, and email.

Memory: inspectable, deletable memory store controlled by Sidekick; agents request reads/writes through Sidekick.

How Dreamer Could Make Money

Dreamer is building an ecosystem business. The intended economics resemble an app store: subscriptions plus commerce take-rate plus a marketplace of premium capabilities. Dreamer also sets aside subscription share to pay tool creators, which is a classic platform move: subsidize supply early to increase variety and quality.

Revenue model:

User subscriptions: Dreamer says beta access is an extended free trial of a paid product.

Premium tool partnerships: commercial services can become premium tools; users get free trial credits.

Marketplace take-rate (implied): a cut of commerce / agent or tool monetization, consistent with the OS/app store analogy.

Dreamer’s distribution is designed to be product-led:

Community-first beta focused on builders; Discord, hackathons, in-product discussions.

Sharing loop: users can share agents with friends/family/coworkers even if they don’t have full accounts.

Tool distribution partnerships: other companies can distribute capabilities as tools; Dreamer frames this as a mutual-user win.

Cross-device embed: home screen widgets, browser homepages, RSS/podcast feed. These create habit loops.

Platform Builders with Scar Tissue

Dreamer’s founding team is conspicuously platform-native: people who have built operating systems, app stores, and design systems used by billions. That is not a guarantee of success; it is, however, the correct scar tissue for an OS-style bet.

David Singleton (Co-founder, CEO): former CTO at Stripe; former VP Engineering at Google; founded Android Wear.

Hugo Barra (Co-founder, CPO in early /dev/agents reporting): former VP of Android product management at Google; led Meta’s Oculus VR products; previously at Xiaomi; co-founded Detect.

Ficus Kirkpatrick (Co-founder, CTO in early reporting): early Android engineer; engineering leader for Google Play; former VP at Meta overseeing VR/AR platforms.

Nicholas Jitkoff (Co-founder, design): principal designer on Material Design; design roles at Dropbox and Figma; worked on Chrome OS and Android design.

The Numbers: What We Know, What We Infer

A diligence checklist for a platform like Dreamer would focus on:

Revenue: subscription ARR, take-rate revenue from premium tools/marketplace, and any enterprise/partner revenue.

COGS: model inference, compute, storage, third-party API/tool costs, and revenue share payouts to creators. (This is where many agent businesses live or die.)

Opex: R&D headcount, trust & safety, support, and community programs (hackathons, moderation).

Unit economics by cohort: builders vs non-builders; heavy vs light agent users; high-cost agents.

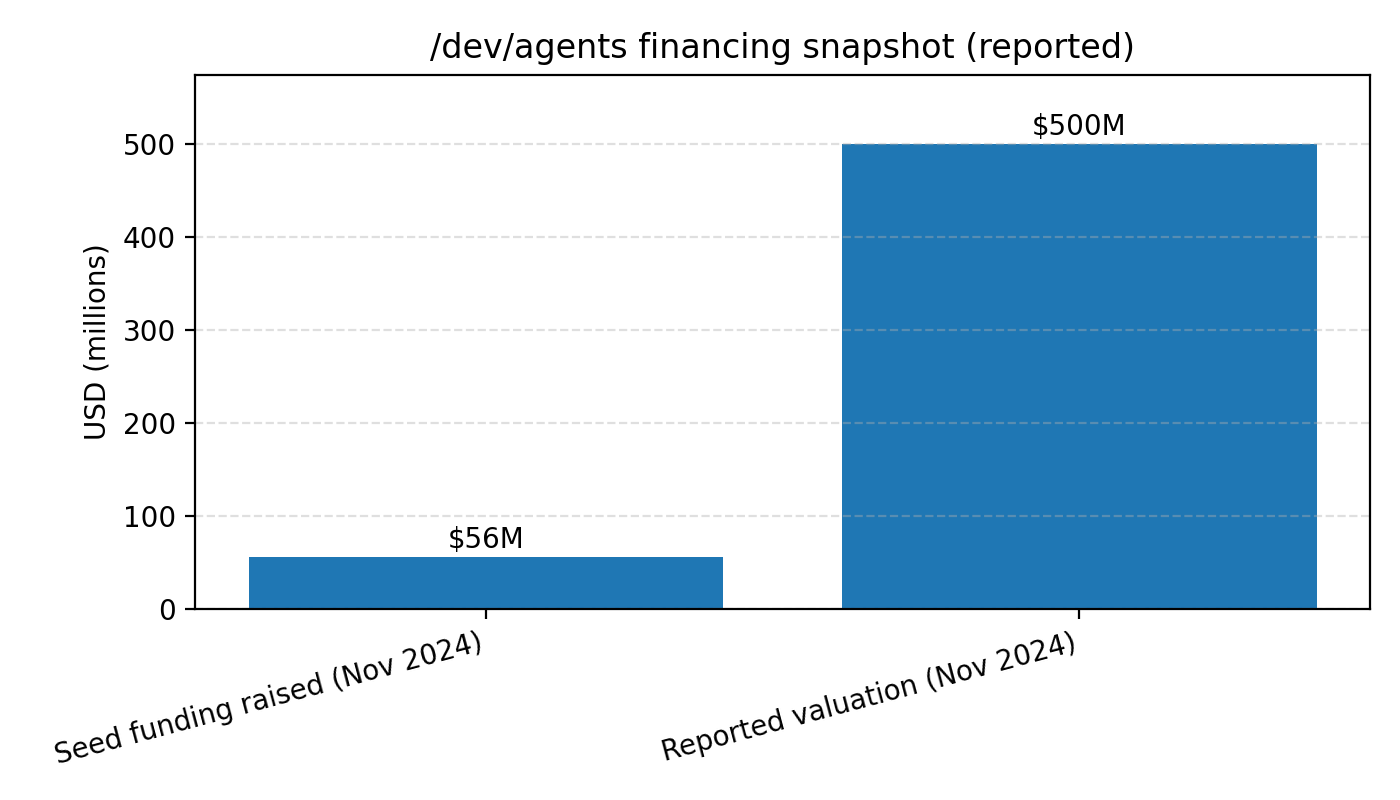

What can be inferred carefully:

Equity financing: /dev/agents raised a $56M seed round (CapitalG + Index co-leads) as announced by CapitalG and reported by TechCrunch.

Cash: proceeds from that round minus operating burn (unknown).

Debt: no public indication of material debt; cannot be ruled out without filings.

Deferred revenue / liabilities: unknown until pricing and subscription billing is public.

The key cash-flow questions for Dreamer’s model:

Does usage (and love) correlate with cost? If the best agents are the most expensive, cash flow will be hostage to popularity.

How quickly can premium tools convert after free trial credits?

Can creator payouts be structured to incentivize efficiency (quality per dollar) rather than raw usage?

What is the working-capital profile if Dreamer becomes a marketplace (payout timing, fraud risk, chargebacks)?

Five Years Out: The Default Layer for Agents

Dreamer’s five-year “if it works” picture is an OS-level replatforming of everyday software:

A default personal interface: your Dreamer homescreen becomes a daily starting point across desktop and mobile, replacing a handful of habitual apps with a handful of personalized agents.

A robust tool marketplace: high-quality integrations (some free, some paid) that let agents take real action across the services people actually use.

A creator economy for agents: tool builders get paid via subscription share; agent builders monetize directly; Dreamer takes an app-store-style cut.

A trust layer for personal data: inspectable memory, granular permissions, and OS-mediated access become a differentiator as agents become more autonomous.

A new software production function: “build by asking” becomes normal for non-engineers, with pros shipping polished agents that others remix.